This is part of a four-part series on Jean-Paul Marat and the first in a study of the history of witch hunts. I’ll be releasing one part every Monday. The first part will always be free, and the rest will have a short preview before it goes behind a paywall. Please consider supporting this venture by becoming a paid subscriber, so I can continue to spend the time to research and write these!

It is a truth almost universally unacknowledged, that witch hunts begin by singling out social outsiders, and then draw to a close when their ringleaders fall victim to their own dirty tricks.

However little known the outcome of their behavior or the public's views may be upon first entering the court of public opinion, this truth is so well fixed in the subconscious insecurity of the bloodthirsty mob that the ringleaders are considered the rightful collateral of the revolution.

Just as "nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition," those caught up in the revolution suffer from so much myopia that they never see how big the target is on their own back. Journalist Jean-Paul Marat is the textbook example of this phenomenon.

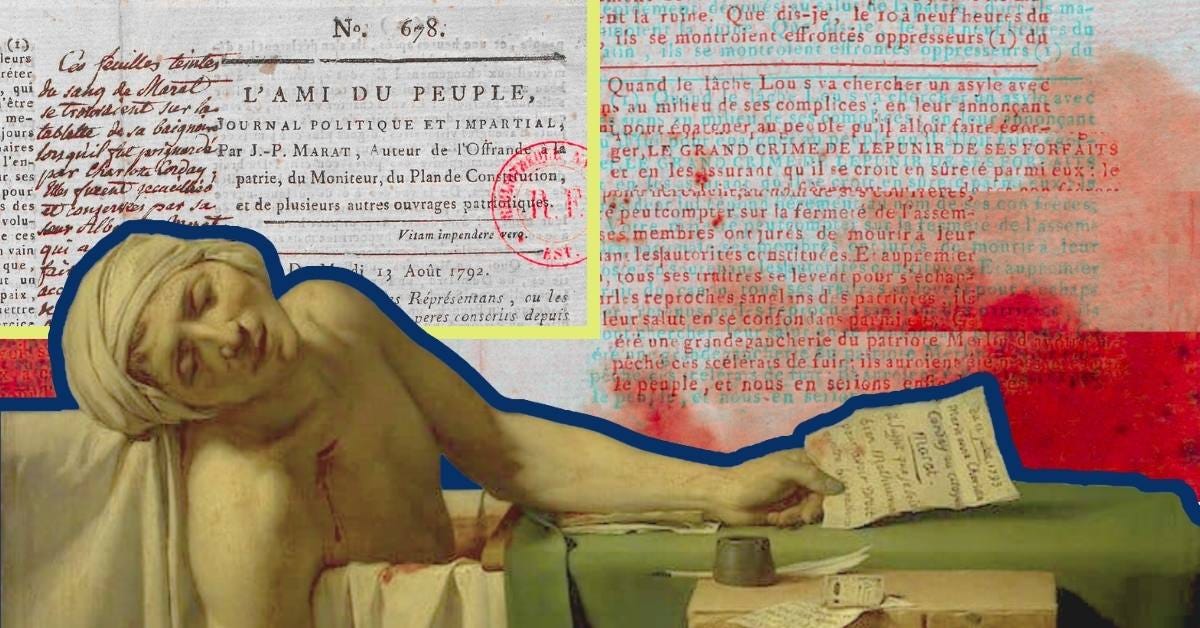

On the 13th of July 1793, Jean-Paul Marat took to his "office" in his bathtub where he conducted most of his business in those days. An unknown skin condition forced him to take regular medicinal baths, so he set up a board over his tub and got to work writing L'Ami du peuple, or The People's Friend, to inspire — and sometimes incite — people to propel the work of liberty, equality and "brotherhood."

A treachery of words

Marat's work was intoxicating. Provided he wasn't hiding from his oppressors, his Jacobin newspaper was published daily. He adopted a fiery yet personal tone that resonated with his readers — you really felt like he was indeed your friend. And the best part? He dropped names.

In such an uncertain time when there was not enough bread (let alone cake) to feed your family, knowing who was to blame for your grievances filled you with a sense of empowerment. The King and Queen sat comfortably in Versailles in immoral squalor while you — a hard-working French citizen — paid oppressive taxes, so they could eat an abundance of sugar, have a multitude of extramarital lovers and abuse the peasant class. At least, that's what L'Ami du peuple had been telling you.

Moreover, Marat published L'Ami du peuple every day. It was like he had informants behind every door listening to forbidden conversations. He published the names of the revolution's enemies like the traitorous Marquis de Lafayette and General Dumouriez. Your suspicions and the whispers you heard about food shortages seem to be confirmed — in print — within days of hearing them. Marat was a hero and a friend of liberty!1

On the other hand, if you were like the 24-year-old Charlotte Corday, the daughter of an impoverished aristocrat, you may have had a different worldview. You would have been reading moderate Girondin papers like Patriote français or works by the English-American writer Thomas Paine. You were more liberal and inspired by the concepts of a free democracy, human rights and separation of powers.

Much like Paine, a Girondin sympathizer, you believed France should do away with its monarchy but that it was wrong to execute the King. After the bloody events of the September Massacres, you and your fellow Girondins grew uneasy about how the Revolution fell into a violent spiral.

All of these papers circulating around Paris seemed to do nothing more than poison people's minds and uphold baseless rumors.

Setting the record straight

On the 9th of July, 1793, Corday left her home in Caen for Paris to meet with Marat in person and settle this dispute once and for all. The violence and mayhem had to stop. Marat couldn't agree more. He once declared to his readers:

"Five or six hundred [aristocratic] heads cut off would have assured your repose, freedom, and happiness. A false humanity has held your arms and suspended your blows; because of this millions of your brothers will lose their lives" — L'Ami du Peuple, 1790

According to him, it wasn't just the King — all noblemen needed to be rooted out of France, preferably by violence. His attacks included members of the King's household like his chief finance minister Jacques Necker, but it didn't stop there. Even a moderate revolutionary like Lafayette — a man generally considered a hero and an important figure in France's alliance with America — wasn’t safe from Marat's sharpened quills.

Cherchez la femme

Corday intended to confront Marat publicly on the 14th of July, 1793, Bastille Day, but the festivities were canceled, and she had to make other arrangements one day early. After running a few errands, she made her way to Marat's house. His wife, Simone, opened the door, and although she was annoyed at her persistence to meet with him, Corday assured her that she had urgent information about a group of Girondin traitors. Simone begrudgingly let her into Marat's "home office." Corday dictated the list of the offending deputies, to which he responded, "Their heads will fall within a fortnight."

Corday pulled a knife out from her pocket and plunged it deep into his chest. He cried out, “Aidez-moi, ma chère amie!” to his wife but was dead within seconds.

Corday made no effort to hide. Simone rushed in; one of Marat's friends seized Corday, and soon a mob formed outside the house to lynch her. But there is no evidence that she made much of a fuss. She even sat serenely for a portrait four days later, just before her appointment with the guillotine. During her trial, she showed she agreed with Marat and his 1790 statement. She was believed to have said at her trial, "I have killed one man to save a hundred thousand."2

Next up…

I’ll release a new part every Monday. Here’s what I have planned:

Part 2: Who was Marat, this wily rascal? You’re about to see some eerie similarities to modern-day journalists, censorship and media culture.

Part 3: The perfect storm that was the French Revolution. The rumor mill starts churning in times of anxiety, uncertainty and disinformation.

Part 4: “On dit…” Why are we so addicted to gossip?!

Don’t miss a single issue. Become a paid subscriber and get access to the full series.

Throughout this series, I cite this paper multiple times. It’s just over 300 pages but brilliant and well worth a read.

Porter, Lindsay. 2017. “Popular Rumour in Revolutionary Paris, 1792-1794.” Www.academia.edu, January. https://www.academia.edu/79068441/Popular_Rumour_in_Revolutionary_Paris_1792_1794

"Charlotte Corday. S.A. Bent, Comp. 1887. Familiar Short Sayings of Great Men." n.d. Www.bartleby.com. Accessed the 1st of August, 2022. https://www.bartleby.com/344/120.html

Your prose is wonderful. I can only aspire to such talent.

Juicy story feels completely current!